The Generative Area:

A Mind for Imagination

During a difficult conversation, you look down and see what looks like a giraffe in the carpet. This phenomenon—the human brain’s ability to find patterns and images even where none exist—is called pareidolia. Research how pareidolia works. Then discuss with your team: would humanity be better off if we only saw what was literally in front of us? When does pareidolia most hurt us—and when does it most help us?

Pareidolia is a psychological phenomenon where the brain perceives familiar patterns—such as faces, animals, or objects—in random or ambiguous stimuli. This happens because the human brain is wired to recognize meaningful shapes, especially faces, as a survival mechanism. Pareidolia isn’t limited to vision—people also experience it with sounds (e.g., hearing voices in static) or even smells.

Examples of pareidolia include seeing faces in clouds, tree bark, or rock formations, spotting shapes in shadows or stains (e.g., "the man in the moon"), hearing hidden messages in reversed audio or white noise.

The brain's fusiform face area (FFA) is highly sensitive to facial patterns, leading us to detect them even where they don’t exist. This tendency likely evolved to help humans quickly identify friends, foes, or threats in their environment. Famous cases include religious figures appearing in food (like the "Virgin Mary grilled cheese toast") or "Mars face" in satellite images.

A mimetolithic pattern is a pattern created on rocks that may come to mimic recognizable forms through the random processes of formation, weathering, and erosion. A well-known example is the Face on Mars, a rock formation on Mars that resembled a human face in certain satellite photos.

Many cultures recognize pareidolic images in the disc of the full moon, including the human face known as the Man in the Moon in many Northern Hemisphere cultures and the Moon rabbit in East Asian and indigenous American cultures.

The Rorschach inkblot test uses pareidolia in an attempt to gain insight into a person's mental state. The Rorschach is a projective test that elicits thoughts or feelings of respondents.

Starting from 2021, an Internet meme emerged for Among Us, where users presented everyday items such as dogs, statues, garbage cans, that looked like the game's "crewmate" protagonists.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Are some settings better for creativity? “Beginnings are contagious there, they’re always setting stages there”—the song “Once Upon a Time in New York City” praises the Big Apple as a place for dreamers, fervent with opportunities for reinvention. Ernest Hemingway and Scott Fitzgerald, among many other writers of their era, hung out with other writers in Paris. Explore the history of the salon, or gatherings where creative and intellectual spirits meet frequently to share and develop ideas, then discuss with your team: is there a place in your country that beckons to the creatively-minded? Has the salon been replaced in the modern world by the Internet—and if so, how?

Oliver & Company is a 1988 American animated musical adventure film produced by Walt Disney. It is inspired by the Charles Dickens novel Oliver Twist. In the film, Oliver is a homeless kitten who joins a gang of dogs to survive in the streets. Among other changes, the setting of the film was relocated from 19th century London to 1980s New York City, Fagin's gang is made up of dogs (one of which is Dodger), and Sykes is a loan shark.

The song is composed by Huey Lewis and the lyrics describe NYC as a place where things are tough, turning pages, and happening and where dreams can come true.

Salons fall in and out of trend depending on the era, but for a solid 400 years or so, from about 1500 – 1900, salons were popular across Europe. The term salon suggests some modicum of regularity, say, weekly, where the enlightened, artistic, disgruntled, the wealthy or ambitious came together for conversation, connection and community.

The earliest roots of salon can be found in Ancient Greece and Rome, the first recorded salons took place in Italy in the 15th Century, and these were a precursor to the Enlightenment Period. They were an opportunity for artists, poets, musicians, thinkers, the Renaissance intellectual glitteratti and their hangers-on, to come together across social classes to hob-nob and share ideas out of the scrutiny of the Roman Catholic Church.

Two noble Italian women, sister-in-laws in Renaissance Italy, were famous for hosting these Italian salons: Isabella d’Este (1474-1533) and Elisabetta Gonzaga (1471 – 1526). The two of them wrote letters back and forth to each other often so the intricacies of their lives are well-documented. Their salons were written about by Baldassare Castiglionein in The Book of the Courtier, which set the standards for how one was to behave, speak and dress at these Italian Renaissance salons. Soon France became infected with the Salon craze.

In Rue St. Honore in Paris, in the 17th and 18th centuries, philosophers, authors, musicians, poets and other interesting and educated people with points of view came together to talk and share ideas about science, politics, literature and art. Female hosts were known as salonniere and became the center of influence, inviting and curating, which was rare in a male-dominant society. Women were not allowed formal education during this time, so the salons also provided an acceptable way to educate oneself. Being invited to a salon was serious business and a sign of social connections.

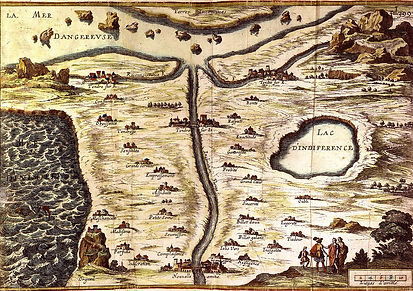

Two well known French salonnierre Catherine de Vivionne, the Marquess de Rambouillet. She was originally from Italy and did not like the French Court so she set up a salon in her estate where people spoke intimately and openly without fear of persecution or punishment. Many famous people came through her salons in the mid-1600s. Another French salonierre or salonista was Madeline de Scudery, known for creating a faminist utopia, where she forbade romantic pursuits, including herself. She said that her salon was its own sovereign country within her heart and created a map to achieve her affection

called La Carte de Tendre. Being part of her salon was a rite of passage for Parisian aristocracy.

Under Napolean, Salons fizzled out of France for the first half of the 1800s with him banishing salonista Germaine de Stael for "teaching people to think who had never thought before or who had forgotten how to think." When salons returned in the later part 1800s, it was focused on modern art exhibitions and literature. They were led by two American expatriates Natalie Clifford Barney and Gertrude Stein, Jewish feminist authors. They

hosted legendary people including Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound. Natalie's place in Paris had a Masonic Temple she dubbed The Temple of Friendship. Her salons ran for 60 years on Friday nights except when she fled to Italy during Nazi occupation. Stein's brother brought in artists including Picasso. Stein also collected Matisse, Cezanne and Renoir paintings. She was deemed the "Mother of Modernism".

Salons in America became popular with the Harlem Renaissance in New York. A'lelia Walker's salon hosted iconic writers like Langston Hughes and Zora Hurston. Walker later launched a direct-to-consumer beauty product company and was the premier arts patron, philanthropist and salonista of her time. She was not alone, other women

were also hosted salons, including author Zora Hurston. Ruth Logan Roberts and Georgia Douglas Johnson gathered leaders to talk about African-American politics, arts and literature.

Salons became popular in the mid-20th century and some became too political and disbanded due to the Red Scare, fear of Communism under the House of Un-American Activities Committee. Salka Viertel's salon in Santa Monica of WWII exiles-tuned-showbiz folks including Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo and Albert Einstein. It seems whenever the world is anxious for new ideas and ready to turn the page, salons start popping up. With Internet forums, has salons lost their appeal?

Consider the neurobiology of imagination: what actually happens in your brain when you are imagining things? Explore the terms below, then hypothesize with your team: how might a person’s imagination be affected if you alter one or more of these elements? How do they relate to emotions, belief, suppositions, and fantasy?

We can define imagery as the production of mental images associated with previous percepts, and imagination as the faculty of forming mental images of a novel character relating to something that has never been actually experienced by the subject but at a great extent emerges from his inner world. The two processes are intimately related and imagery can arguably be considered as one of the main components of imagination. Two concepts related to imagination is exaptation and redeployment. Exaptation is when a trait or feature, or structure of an organism that takes on a new function when none previously existed or that differs from its original function, the brain structure is reused for another purpose. So, neural function were originally designed to help perform certain functions like motor skills, but later developed into "tinkering" combined mental perceptions and concepts to create new "mental objects."

Imagery: the production of explicit or implicit mental pictures or images.

imagination: the act or power of forming mental images that is not actually present or directly experienced.

Neuronal systems have two capabilities: to perform a function and to create a internal theater of the object through internal visualization. Different neurons have different functions and many are involved in the process of imagination.

One critical type is mirror neurons, which mirror the actions you observe inside your own brain. Neuroscientists suggest that these systems have been through evolution to develop into imaginative simulations for emotions, actions and experience.

Another key concept is default mode network (DMN) which can integrate various sensory inputs, like when we are daydreaming. It makes up our inner theater where we construct alternate realities, and internal narratives and future scenarios - our inner world.

In mammals with large brains, Von Economo neurons (VEN), a large spindle-shaped neurons, play a role in long-range fast information

transfer and integration along with specific projections. It is responsible for self-awareness, emotions, and complex decision-making, helping us imagine ourselves in different roles.

Last but not the least, functional modules in the brain can be assembled to form mosaics capable of highly integrated actions. They work through both writing transmission (direct connections) and also volume transmissions (signal diffusing through brain fluids). Astrocytes and the extracellular matrix regulate these connections. There is not straight forward explanation, it is what neuroscientists call interaction dominant dynamic where one change can trigger other changes in function. These in combination allows for imagination to be unique and unexpected for everyone, ranging from creative ideas to personal emotions drawing from different experiences, memories and feelings.

Memory is deeply intertwined with emotions, beliefs, suppositions, and fantasy—shaping how we recall the past and interpret reality. Some key concepts to understand how memory works. Emotional memories are stronger: The amygdala (emotion center) and hippocampus (memory hub) work together, making emotionally charged events (joy, trauma) easier to recall. Memory is also triggered by your mood and it's called mood-congruent recall: Being sad makes you more likely to remember sad events (and vice versa). Also, our memory is not perfect, rather being distorted by emotions. Strong feelings can amplify or alter memories (e.g., remembering a childhood birthday as "perfect" despite minor mishaps).

Linking back to other WSC related concepts, memory has preferences. Because of confirmation bias. We unconsciously favor memories that align with our beliefs. And we sometimes shift our memories to adapt to new ideas we have about ourselves. In some people, false memories can override real memories. Sounds a little like brainwashing.

When details are fuzzy, the brain inserts assumptions and fills in the details, this is called schemas fill gaps. Vivid imagination can make it feel like something is a memory. In terms of fantasy, memory can play tricks on us, mixing truths with imagination, for example forgetting whether a detail came from experience, a movie, or a daydream.

In the philosophy of mind, neuroscience, and cognitive science, a mental image is an experience that, on most occasions, significantly resembles the experience of "perceiving" some object, event, or scene but occurs when the relevant object, event, or scene is not actually present to the senses. There are sometimes episodes, particularly on falling asleep (hypnagogic imagery) and waking up (hypnopompic imagery), when the mental imagery may be dynamic, phantasmagoric, and involuntary in character, repeatedly presenting identifiable objects or actions, spilling over from waking events, or defying perception, presenting a kaleidoscopic field, in which no distinct object can be discerned. Mental imagery can sometimes produce the same effects as would be produced by the behavior or experience imagined.

Historically, the notion of a "mind's eye" goes back at least to Cicero's reference to mentis oculi. A biological basis for mental imagery is found in the deeper portions of the brain below the neocortex. Researchers also found significant positive correlations between visual imagery vividness and the volumes of the hippocampus and primary visual cortex. Common examples of mental images include daydreaming and the mental visualization that occurs while reading a book. Another is of the pictures summoned by athletes during training or before a competition, outlining each step they will take to accomplish their goal. When a musician hears a song, they can sometimes "see" the song notes in their head, as well as hear them with all their tonal qualities.

Perception relies on intricate nervous system functions, yet it feels effortless because most processing occurs unconsciously. Since the 19th century, experimental psychology has advanced our understanding of perception through diverse methods. Psychophysics measures how physical sensory inputs translate into subjective experience, while sensory neuroscience explores the brain's role in perception. Computational approaches analyze perception as an information-processing system. Philosophers, meanwhile, debate whether qualities like color or smell exist independently or are constructed by the mind.

The process of perception begins with an object in the real world, known as the distal stimulus or distal object. By means of light, sound, or another physical process, the object stimulates the body's sensory organs. These sensory organs transform the input energy into neural activity—a process called transduction.This raw pattern of neural activity is called the proximal stimulus. These neural signals are then transmitted to the brain and processed. The resulting mental re-creation of the distal stimulus is the percept.

A worldview (also world-view) or Weltanschauung is said to be the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual's or society's knowledge, culture, and point of view. However, when two parties view the same real world phenomenon, their worldviews may differ, one including elements that the other does not. A worldview can include natural philosophy; fundamental, existential, and normative postulates; or themes, values, emotions, and ethics.

A person’s worldview—their fundamental understanding of reality, meaning, and values—profoundly shapes their emotions, beliefs, suppositions, and fantasies by acting as a lens through which they interpret experiences. For example, an optimistic worldview may foster positive emotions (e.g., hope in adversity), while a pessimistic one may amplify anxiety or resentment. Beliefs are directly filtered through this framework (e.g., seeing human nature as inherently good vs. selfish), and suppositions (unconscious assumptions) are drawn from its logic (e.g., trusting authority vs. expecting corruption). Even fantasies are constrained or empowered by worldview—someone who views the universe as mechanistic might imagine technological utopias, while a spiritually oriented person might fantasize about transcendent unity with nature.

In the human brain, the cerebral cortex consists of the larger neocortex and the smaller allocortex, respectively taking up 90% and 10%. The neocortex is made up of six layers, labelled from the outermost inwards, I to VI. The neocortex is the outermost layer of the brain’s cerebral hemispheres and is responsible for higher-order cognitive functions, including sensory perception, conscious thought, language, and decision-making. Structurally divided into six layers, it processes complex information by integrating inputs from other brain regions, such as the hippocampus (critical for memory formation) and the amygdala (involved in emotion). The neocortex plays a key role in memory by storing and retrieving declarative memories (facts and events) and enabling semantic knowledge (general world understanding). It also supports fantasy by allowing mental simulation—imagining future scenarios, creative ideas, or fictional narratives through the recombination of stored memories. Without the neocortex, abstract thinking and self-reflection would be impossible.

The thalamus is a small, dual-lobed structure deep in the brain that acts as the brain’s "relay station," filtering and directing sensory and motor signals (except smell) to the cerebral cortex. It regulates consciousness, sleep, and alertness, but it also plays a subtle yet crucial role in memory, daydreaming, and emotions. For memory, the thalamus works with the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex to help consolidate and retrieve episodic memories (personal experiences). Damage to certain thalamic regions, like the mediodorsal nucleus, can cause amnesia or confabulation (fabricated memories), highlighting its role in memory accuracy.

In daydreaming, the thalamus modulates the brain’s default mode network (DMN)—a system active during mind-wandering—by controlling cortical arousal. It helps shift focus between external stimuli and internal thoughts, allowing fantasies to unfold without sensory disruption. For emotions, the thalamus connects the amygdala (fear/pleasure center) and prefrontal cortex (rational control), influencing how emotional memories are processed. For example, during trauma, the thalamus may overampflying sensory

to the amygdala, creating vivid, intrusive memories. In summary, the thalamus quietly orchestrates the balance between reality and imagination, grounding emotions and memories in sensory context while permitting the mind to wander.

The frontal lobe is the largest lobe of the brain, located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere. The frontal lobe contains most of the dopaminergic neurons in the cerebral cortex. The dopaminergic pathways are associated with reward, attention, short-term memory tasks, planning, and motivation. Dopamine tends to limit and select sensory information coming from the thalamus to the forebrain

Cognitive Functions: It is involved in thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making.

Motor Function: The frontal lobe is responsible for controlling voluntary movements.

Speech Production: It plays a key role in the production of speech.

Social Interactions: It helps in building social relationships and understanding ethics.

Overall, the frontal lobe is essential for higher cognitive functions and personality expression.

The REM phase is also known as paradoxical sleep (PS) and sometimes desynchronized sleep or dreamy sleep, because of physiological similarities to waking states including rapid, low-voltage desynchronized brain waves. REM sleep is physiologically different from the other phases of sleep, which are collectively referred to as non-REM sleep (NREM sleep, NREMS, synchronized sleep). The absence of visual and auditory stimulation (sensory deprivation) during REM sleep can cause hallucinations. REM and non-REM sleep alternate within one sleep cycle, which lasts about 90 minutes in adult humans. As sleep cycles continue, they shift towards a higher proportion of REM sleep. The transition to REM sleep brings marked physical changes, beginning with electrical bursts called "ponto-geniculo-occipital waves" (PGO waves) originating in the brain stem. REM sleep occurs 4 times in a 7-hour sleep.

REM (Rapid Eye Movement) sleep is the stage most strongly linked to vivid, narrative-like dreams due to heightened brain activity resembling wakefulness. During REM, the brain's limbic system (emotion center) and

.jpg)

.jpg)

visual cortex are highly active, while the prefrontal cortex (responsible for logic and self-awareness) is dampened—explaining dreams' emotional, bizarre, and often illogical nature. This stage also paralyzes voluntary muscles (via brainstem signals) to prevent physical acting out of dreams. Studies show that disrupting REM sleep impairs dream recall and emotional processing, suggesting its critical role in integrating memories, emotions, and creative thought through dreaming.

Research drugs that stimulate the imagination, then discuss with your team: should all these be considered illegal hallucinogens? Be sure to consider how and to what degree a hallucination varies from a simulation, a rehearsal, or other acts of the imagination. For instance, when is a daydream a hallucination?

Daydreaming is a stream of consciousness that detaches from current external tasks when one's attention becomes focused on a more personal and internal direction. Various names of this phenomenon exist, including mind-wandering, fantasies, and spontaneous thoughts. There are many types of daydreams – however, the most common characteristic to all forms of daydreaming meets the criteria for mild dissociation. The term daydreaming is derived from clinical psychologist Jerome L. Singer, whose research created the foundation for nearly all subsequent modern research.

Daydreaming consists of self-generated thoughts comprising three distinct categories: thoughts concerning the future and oneself, reflections on the past and others, and the emotional tone of experiences. Singer established three different types of daydreaming and their characteristics, varying in their cognitive states and emotional experiences. These included positive constructive daydreaming, characterized by constructive engagement, planning, pleasant thoughts, vivid imagery, and curiosity; guilty-dysphoric daydreaming, marked by obsessive, guilt-ridden, and anguished fantasies; and poor attentional control, reflecting difficulty focusing on either internal thoughts or external tasks.

Daydreams are long, detailed, and pleasurable fantasies to which a person willingly (albeit compulsively) devotes huge portions of their waking life. Hallucinations, by contrast, are sudden and chaotic intrusions into reality that can be uncontrollable and alarming.

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the compelling sense of reality. They are distinguishable from several related phenomena, such as dreaming (REM sleep), which does not involve wakefulness; pseudohallucination, which does not mimic real perception, and is accurately perceived as unreal; illusion, which involves distorted or misinterpreted real perception; and mental imagery, which does not mimic real perception, and is under voluntary control. Hallucinations also differ from "delusional perceptions", in which a correctly sensed and interpreted stimulus (i.e., a real perception) is given some additional significance.

,The cause of hallucinations often has to do with trauma or abnormal or impaired brain function, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Daydream is linked to personality traits including capacity for absorption, to the great extent that one become immersed in a task and other sensory experiences fade. Addictive personality is also one of the traits that may lead to daydreaming. Social anxiety or worried about social interaction also leads to less social skills and daydreaming.

While how to become more imaginative is a question most frequently answered by self-help publications and clinics that also offer derriere implants, some mainstream treatments and techniques do exist and are practiced in the real world. Explore the following approaches and terms then discuss with your team: which do you think would be most effective?

Paul Seli, PhD, is falling asleep. As he nods off, a sleep-tracking glove called Dormio, developed by scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, detects his nascent sleep state and jars him awake. Pulled back from the brink, he jots down the artistic ideas that came to him during those semilucid moments.

Seli is an assistant professor of psychology and neuroscience at the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences and also an artist. He uses Dormio to tap into the world of hypnagogia, the transitional state that exists at the boundary between wakefulness and sleep. In a mini-experiment, he created a series

of paintings inspired by ideas plucked from his hypnagogic state and another series from ideas that came to him during waking hours. Then he asked friends to rate how creative the paintings were, without telling them which were which. They judged the hypnagogic paintings as significantly more creative. “In dream states, we seem to be able to link things together that we normally wouldn’t connect,” Seli said. “It’s like there’s an artist in my brain that I get to know through hypnagogia.”

At an individual level, creativity can lead to personal fulfillment and positive academic and professional outcomes, and even be therapeutic. Beyond those individual benefits, creativity is an endeavor with implications for society, said Jonathan Schooler, PhD, a professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “Creativity is at the core of innovation. We rely on innovation for advancing humanity, as well as for pleasure and entertainment,” he said. “Creativity underlies so much of what humans value.”

While creativity is highly valued, researchers are having a difficult time defining what is creativity and how to measure it. There are new neuroimaging technology to help, but unless there is a clear definition, it remains a challenge. One way is divergent thinking - coming up with as many alternative solutions as possible. The standard test is by J. P. Guilford, PhD, then president of APA (American Psychology Association) who asked participants to come up with a novel use for common object such as a brick. This doesn't really help as it only measures output, so scientists are looking at what goes on inside the brain. What they discovered is that the process of being creative involves the interaction of discrete brain regions, coordination between cognitive control network and the default mode network. The cooperation of those

networks may be a unique feature of creativity, Adam Green, PhD, a cognitive neuroscientist at Georgetown University and founder of the Society for the Neuroscience of Creativity said. “These two systems are usually antagonistic. They rarely work together, but creativity seems to be one instance where they do.” He also found that the area called the frontopolar cortex in the brain's frontal lobes is associated with creative thinking.

The frontopolar cortex is located at the frontal pole of each frontal lobe and contains Brodmann area 10. It is involved in high-order cognition, including reasoning, problem-solving, and multitasking.

Creativity is also different from person to person and cognitive scientist have identified two systems. Creativity can be one or a combination of both. Researcher Kunios used electroencephalography (EEG) to examine the minds of jazz musicians as they improvise.

1) System 1 is quick unconscious thoughts - aha moments - highly experienced musicians generate ideas almost instinctively from the left posterior part of the brain.

2) System 2 is thinking that is slow, deliberate and conscious. - less experienced musicians used the right frontal region to devise and analyze creatively

There is also a relationship between creative insight and brain's reward system. When you feel a AHA moment, you brain feels a burst of activity in the orbital frontal cortex, like you indulged in delicious food or addictive drug. Humans are tuned to feel pleasure from creativity - maybe linked to our adaptive skills as a species.

Active imagination is a way of using dreams and creative thinking to unlock the unconscious mind. Developed by Carl Jung between 1913 and 1916, one of the most influential psychologist and scholars of the 20th century. He used images from vivid dreams that the person has remembered upon waking.

Then, whilst the person is relaxed and in a meditative state, they recall these images, but in a passive way. Allowing their thoughts to remain on the images but letting them change and manifest into whatever they happen to become.

These new images can be expressed through various mediums, including writing, painting, drawing, even sculpting, music, and dance. The object is to let the mind free associate. This then allows our unconscious mind the chance to reveal itself.

-Portrait-Portr_14163_(cropped)_tif.jpg)

Hypnagogia is the transitional state from wakefulness to sleep, also defined as the waning state of consciousness during the onset of sleep. Its corresponding state is hypnopompia – sleep to wakefulness. Mental phenomena that may occur during this "threshold consciousness" include hallucinations, lucid dreaming, and sleep paralysis.

In this state, creative people can form new connections between separate contexts, leading towards solutions based on intuition — and ones you might not consider with a rational, Slack-distracted mind. In his book 50 Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, Salvador Dali — perhaps the most famous fan of the hypnagogic

state — prescribed his napping technique to all artists as a problem-solving hack:

“You will secretly, in the very depths of your spirit, solve most of [your work’s] subtle and complicated technical problems, which in your state of waking consciousness you would never be humanly capable of solving.”

Part of the explanation behind this incredible finding is our shift in brainwave states. When we enter a hypnagogic state, we move from alpha waves

(relaxed wakefulness) to theta waves (deep creativity and problem-solving). We move past the over-editing filter of our conscious mind. Short naps, bedside journal, meditation are all ways to reach the perfect hypnagogia state and unlock your creativity.

Our minds are never idle. When not focused on doing a specific task or achieving a goal, we daydream, fantasize, ruminate, reminisce about something in the past, or worry about something in the future. In fact, research with thought-sampling techniques has shown that an average of 47% of our time is spent with our mind wandering. Think of it: nearly half our waking hours! Research also suggests that mind wandering is not time wasted but a constructive mental tool supporting creativity, problem-solving, and better mood.

One of the most meaningful developments in recent neuroscience is the serendipitous discovery of the brain network that hosts our mind wandering: substantial cortical regions clustered together in the brain’s “default mode network.”

Wandering is what our brain does by default. So, logic dictates that if our brains dedicate so much energy to mind wandering, mind wandering should play an important role.

Hypnosis is a human condition involving focused attention (the selective attention/selective inattention hypothesis, SASI), reduced peripheral awareness, and an enhanced capacity to respond to suggestion. During hypnosis, a person is said to have heightened focus and concentration and an increased response to suggestions. Hypnosis usually begins with a hypnotic induction involving a series of preliminary instructions and suggestions. The use of hypnosis for therapeutic purposes is referred to as "hypnotherapy", while its use as a form of entertainment for an audience is known as "stage hypnosis"

Meditation is practiced in numerous religious traditions, though it is also practised independently from any religious or spiritual influences for its health benefits. Guided meditation is a form of meditation which uses a number of different techniques to achieve or enhance the meditative state. It may simply be meditation done under the guidance of a trained practitioner or teacher, or it may be through the use of imagery, music, and other techniques. Meditation lowers heart rate, oxygen consumption, breathing frequency, stress hormones, lactate levels, and sympathetic nervous system activity (associated with the fight-or-flight response), along with a modest decline in blood pressure. For meditators who have practiced for years, breath rate can drop to three or four breaths per minute and "brain waves slow from the usual beta (seen in waking activity) or alpha (seen in normal relaxation) to much slower delta and theta waves".

Psychological distance is the degree to which people feel removed from a phenomenon. Distance in this case is not limited to the physical surroundings, rather it could also be abstract. Distance can be defined as the separation between the self and other instances like persons, events, knowledge, or time. This has since been revised to include four categories of distance: spatial, social, hypothetical, and informational distances. Further studies have concluded that all four are strongly and systemically correlated with each other. According to researcher psychological distance can facilitate decision-making and creative cognition, offering a potential mechanism for enhancing creative-idea selection.

1. Temporal Distance: It refers to how far away something is in time, whether in the past or future. Remember that vacation example? That’s temporal distance in action. Events in the distant future or past often feel less “real” to us than those in the present.

2. Spatial Distance: Think about how differently you might feel about a natural disaster happening in your hometown versus one occurring on the other side of the world. Spatial distance can significantly impact our emotional responses and decision-making processes.

3. Social Distance: It could be based on factors like personal relationships, cultural similarities, or shared experiences. The concept of propinquity psychology explores how physical and psychological closeness shapes our relationships, which is closely related to social distance.

4. Hypothetical Distance: For instance, winning the lottery might feel very hypothetically distant, while getting a promotion at work might feel more hypothetically close.

One used by writers is called “writing with constraints”. If their options are limited—for instance, if they cannot use the letter A in a story—someone struggling to put words on a blank page might dodge that first paralyzing moment of decision-making. Artificial limitations “provide a certain level of texture against which a metaphorical match can more easily be struck,” says the writer Matthew Tomkinson. Many traditional poetic forms—especially strict ones, such as haiku—are examples of this approach. Read about others across different genres, including those of the French Oulipo movement, then learn more about the selections below. Afterward, discuss with your team: should more creators use this technique? When they do, should it be advertised to the public? Would you want to try it for your World?

From Dashiel Carrera, Matthew Vollmer, Matthew Tomkinson, Julie Carr, and Jean Marc Ah-Sen

For writers, the power of creative constraints may not stem from the limitations themselves, but rather from how they counterbalance certain unproductive tendencies. These constraints can also serve as a tool for writers to clarify the goals and requirements of a specific project. In the five works featured in this collection—covering fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction—creative constraints helped define the evolving boundaries of the writing process and illuminated a clear direction for progress.

Matthew Vollmer, Inscriptions for Headstones, (Outpost 19)

I decided to write multiple epitaphs (instead of just one) from a third person perspective and to begin each epitaph with a phrase that would signal to the reader that we were undoubtedly in epitaph territory, like “here lies X” or “R.I.P. Y” or “this stone marks the final resting place of Z,” and instead of preserving the inherently pithy quality of the form, which often seemed to relay only the most basic of information regarding the deceased—like “beloved father and husband.”

Famous painter David Hockney once said, which was that, “if you were told to make a drawing of a tulip using five lines or one using a hundred, you’d be more inventive with the five.”

Matthew Tomkinson, oems, (Guernica Editions)

Before writing anything, I first resolved to flatten the dictionary. This entailed copy-pasting the contents of the Merriam Webster into a spreadsheet, and then removing all words containing tall letters (b, d, f, g, h, j, k, l, p, q, t, y). What remained was a curated list of flat words such as “sunrise” and “consciousness,” with which I composed the book. In essence, then, my chosen form fits the definition of a lipogram (a work that omits certain letters).

Julie Carr, Real Life: An Installation, (Omnidawn)

One day in a moment of confusion, I fund myself numbering my lines. When I got to fourteen, the number of lines in a sonnet, I stopped. I titled the poem “Into it,” for it had allowed me back “in” to the writing. I found that within the cool comfort of the 14-line limit, I could pack almost anything I wanted. Like a child in a playground, the poem felt protected, even as it went wild. “The real renews itself each year/ I’ll do whatever the radios suggest,” I wrote in lines numbered 4 and 5. After that, I wrote dozens of fourteen-line poems, each with their lines deliberately numbered.

Jean Marc Ah-Sen, Disintegration in Four Parts, (Coach House Books)

I came up with a quote that could rally potential writers together—“all purity is created by resemblance and disavowal”—and then sought out the best literary fiction practitioners I knew to interpret the cryptic dictum. We individually abided by a 10,000 word count and an ambitious four month deadline. These constraints were really on account of my unfledged status in writing. I thought I could turn this project into a “clinker-built” writing apprenticeship for myself, where my work could somehow overlap with others and participate in the rigors of a creative writing program.

One sound in Chinese could have a multiple number of meaning. This poem’s name, in Chinese characters, is 施氏食獅史. In Pinyin, that would be “Shī shì shí shī shǐ.” This text was composed by the Chinese-American linguist, scholar, and poet Yuen Ren Chao in the 1930s. Mr. Chao also significantly contributed to the modern study of Chinese grammar. The sound “shi” is the only sound in the poem. You find it 94 times (in some versions, there are only 92). Only the tones differ. That’s right! Mr. Chao wrote this poem as a linguistic demonstration. Therefore, the poem shows that writing a one-syllable text that means something is possible. That’s because Chinese is a tonal language. So, the same syllable can have a different tone and correspond to a different character. Pawwsitively fascinating.

« The Lion-Eating Poet in the Stone Den »

In a stone den was a poet called Shi Shi, who was a lion addict and had resolved to eat ten lions.

He often went to the market to look for lions.

At ten o’clock, ten lions had just arrived at the market.

At that time, Shi had just arrived at the market.

He saw those ten lions and, using his trusty arrows, caused the ten lions to die.

He brought the corpses of the ten lions to the stone den.

The stone den was damp. So he asked his servants to wipe it.

After wiping the stone den, he tried to eat those ten lions.

When he ate, he realized that these ten lions were, in fact, ten stone lion corpses.

Try to explain this matter.

The poem "No So Fine" by Marianne Moore offers a unique comparison between inanimate objects and living creatures. It contrasts the stillness of the fountains of Versailles with the beauty of a china swan, suggesting that the artificial can surpass the natural in terms of aesthetics. This theme of artifice vs. nature is a recurring one in Moore's work, as seen in poems like "Poetry" and "The Steeple-Jack."

Moore also uses language to evoke the grandeur and opulence of the French court. The poem is filled with rich, evocative words like "chinz," "fawn-brown," and "gold," which create a sense of luxury and extravagance. This use of language is characteristic of Moore's work, which often explores themes of wealth and status.

The poem also reflects the time period in which it was written. Moore was writing during the early 20th century, a time of great social and political change. The poem's focus on artifice and luxury can be seen as a reflection of the materialism and excess of the era.

Ernest Vincent Wright (1872 – October 7, 1939) was an American writer known for his book Gadsby, a 50,000-word novel which (except for four unintentional instances) does not use the letter E. A work that deliberately avoids certain letters is known as a lipogram. The plot revolves around the dying fictional city of Branton Hills, which is revitalized as a result of the efforts of protagonist John Gadsby and a youth organizer.

summary of Gadsby Chapter 1: The chapter discusses the potential of youth and the importance of nurturing a child's inquisitive nature. It emphasizes that children, though often underestimated, have the capacity for deep thought and creativity. The protagonist, John Gadsby, seeks to revitalize the stagnant small town of Branton Hills, which has grown complacent and resistant to change.

Gadsby believes that to foster growth, the town needs a champion to inspire its youth. He gathers a group of enthusiastic students to form an organization aimed at improving their community. They tackle various issues, such as inadequate infrastructure and a lack of recreational areas, by rallying support from the town’s adult population, including wealthy residents.

Through determination and collaboration, they initiate projects like a park and a public library, demonstrating that with the right guidance, the energy and ideas of youth can lead to significant improvements in their environment. Gadsby's vision reflects a belief in the power of community and the necessity of engaging young minds to create a better future.

.jpg)

“Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” is a poem by the Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, first published in 1951. Though the poem was dedicated to Thomas’s father, it contains a universal message. The poem encourages the dying—the sick and the elderly—to fight bravely against death. The poem also celebrates the vibrancy and energy of human life, even though life is fragile and short.

The Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) was something of a prodigy. He published many of his intense, idiosyncratic poems when he was just a teenager. While his stylistic inventiveness places him among the modernists, his pantheistic feelings about nature and his passionate sincerity also mark him as a descendent of 19th-century Romantic poets like William Blake and John Keats (both of whom he read enthusiastically). He also admired his contemporaries W.B. Yeats and W.H. Auden , who, like him, often wrote of the "mystery" behind everyday life (though in very different ways).

"Do Not Go Gentle into That Night” was written sometime in the late 1940s and early 1950s—the years just after the end of World War II. For Thomas, a Welsh poet, the war would’ve been an important presence in his life: throughout the war, the Nazis bombed towns and cities across the United Kingdom. The years after the war were dedicated to rebuilding—a project that sometimes required reconstructing entire cities from the rubble. Thomas would have seen the human cost of the war firsthand, both in terms of soldiers who died in battle as well as the civilians who died in air raids.

Kimiko Hahn (born July 5, 1955) is an American poet and distinguished professor in the MFA program of Queens College, CUNY. Her works frequently deal with the reinvention of poetic forms and the intersecting of conflicting identities.

This short poem is witty by giving a secondary message through the bold text at the end of each line. The poem deals with the them of climate change and our ignorance of it, how we are unable to part with fossil fuels. It shows that everything is interconnected and that "The Whale Already Taken Got Away. The Moon Alone."

Disney’s theme park designers are infamously branded as “Imagineers”—in just one of the many ways that imagination is celebrated in popular culture. Check out the following works, then discuss with your team: what perspective do they take on imagination? Do they share any common messages?

Despite what you’ve heard, the word “imagineering” is not unique to Disney. In fact, it’s a phrase that was first used in World War II corporate propaganda.

One of Alcoa’s many ads promoting “imagineering,” a concept it embraced nearly two decades before Disney did. Some of the ads took a feel much closer to propaganda. (Internet Archive). Imagineering started as a wartime slogan for the aluminum industry to promote itself, with no Disney in sight. (left) It was printed November, 1942 by the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa), in an effort to encourage the public purchase of war bonds.

During WWII, it became the theme of the campaign for the aluminum industry, trying to highlight on engineering for America's future. It was only later that "imagineering" became a word for the entertainment industry and used widely by Walt Disney. In fact, the word later evolved into different meanings see book covers on the left.

At Disney imagineering was a massive cultural force that drives forward its theme filmmaking and theme park efforts, that there is something truly special and unique about someone who can cut it as an Imagineer. But despite Disney owning a trademark on the term, which it registered in the late 1980s, the prior art is strong for this specific phrase.

Imagineering has become many things, including a company that makes video games, a song, a circuit board company, an education company and toy company.

"Imagination" is a popular song with music written by Jimmy Van Heusen and the lyrics by Johnny Burke. The song was first published in 1940. The two best-selling versions were recorded by the orchestras of Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey in 1940. Jimmy Van Heusen originally wrote the song when he was a teenager, but with different words. When he later played the tune for Johnny Burke (without the lyrics), Burke wrote the "Imagination" lyrics.

"Imagination" describes a person's mind wandering and daydreaming, and the feelings he imagines changes his mood. The imagination also features fantasy and role playing, like a person thinking of something very unlikely and out of reality.

"Pure Imagination" is a song from the 1971 film Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. It was written by British composers Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley specifically for the movie. It was sung by Gene Wilder, who played the character of Willy Wonka. Bricusse has stated that the song was written over the phone in one day. The song has a spoken introduction. This song has been widely covered by artists such as Josh Groban, Harry Connick, Fiona Apple, Buckethead and many others. It has also been covered in the hit Fox show ‘Glee’.

Hold your breath

Make a wish

Count to three

Come with me and you'll be

In a world of pure imagination

Take a look and you'll see

Into your imagination

We'll begin with a spin

Traveling in the world of my creation

What we'll see will defy

Explanation

If you want to view paradise

Simply look around and view it

Anything you want to, do it

Want to change the world?

There's nothing to it

"Imagine" is a song by English musician John Lennon (from the Beatles) from his 1971 album of the same name. The best-selling single of his solo career, the lyrics encourage listeners to imagine a world of peace (during the Vietnam War), without materialism, without borders separating nations and without religion. It peaked at #3 on the Billboard Hot 100, and remains one of the most well-known and respected songs worldwide. Lennon later credited his wife Yoko as a contributor for the lyrics. Imagine" has consistently been widely praised since its release, while also garnering controversy due to its lyrics. More than 200 stars over the years have covered the song and referencing Lennon as their musical inspiration. The song has also become a theme song for world events ranging from the Olympics to advocacy for refugees during the Ukrainian War. The song remains controversial, as it has been since its release, over its request to imagine "no religion too"

Evanescence is an American rock band founded in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1995 by singer/pianist Amy Lee and guitarist Ben Moody. Released as a promo single in Spain, “Imaginary” describes the artist’s strong desire to live in a dream rather than live in reality. The song uses imagery to describe the dream world and help listeners imagine it too. The title of the song is fitting as the dream world that is described only exists in the persona’s mind and is imaginary. This song was rerecorded for Fallen, but was initially released on their first EP in 1998.

Ah-ah-ah-ah Paper flowers

Ah-ah-ah-ah Paper flowers

I linger in the doorway

Of alarm clock screaming monsters calling my name

Let me stay where the wind will whisper to me

Where the raindrops, as they’re falling, tell a story

In my field of paper flowers (Ah-ah-ah-ah)

And candy clouds of lullaby (Paper flowers)

I lie inside myself for hours (Ah-ah-ah-ah)

And watch my purple sky fly over me (Paper flowers)

Swallowed up in the sound of my screaming

Cannot cease for the fear of silent nights

Oh, how I long for the deep sleep dreaming

The goddess of Imaginary light

John, you’re right

It’s good to know you’re bright

For intellect can wash away confusion

Georgie sees, and Annabel agrees

Most folderol’s an optical illusion

You three know it’s true

That one plus one is two

Yes, logic is the rock of our foundation

I suspect, and I’m never incorrect

That you’re far too old to give in to imagination

No, not yet

Some people like to splash and play

Can you imagine that?

And take a seaside holiday

Can you imagine that?

Too much glee leaves rings around the brain

Take that joy and send it down the drain

Some people like to laugh at life

And giggle through the day

They think the world’s a brand new shiny toy

And if while dreaming in the clouds

They fall and go ker-splat

Although they’re down and bent in half

They brush right off and start to laugh

Can you imagine that?

The 2016 short film Shelter portrays a girl living alone in a simulation, passing her days imagining virtual worlds—until one day a letter arrives explaining how she got there. This film is one of many that explores how the human mind can remain active in a world without physical stimuli—which could be your fate if humans achieve digital immortality in our lifetimes. Learn more about the brain activities of coma patients and those living in isolation, then discuss with your team: what would it take for you to be happy living without a body?

"Shelter" is a song by American DJ and record producer Porter Robinson and French DJ and record producer Madeon, released as a single on August 11, 2016. In October 2016, a music video, produced in collaboration with A-1 Pictures, was released. The music video is based on an original story written by Robinson, the video is produced in a short film format.

The video's plot follows 17-year-old Rin (voiced by Sachika Misawa) who lives alone inside a futuristic simulation. She maintains control of the simulation and the virtual world around her through a tablet on which she can draw scenes that the world around her will then create in a three-dimensional environment. She continues on like this for many years, living a peaceful but lonely life. All of a sudden, she experiences scenes before her that she hasn't created. As an invisible observer, Rin witnesses her life as a 10-year-old child living in Tokyo. Through a series of newsreels and images, it is learned that at this time a moon-sized planetary object is on a collision course with Earth. Rin's father Shigeru dedicates a large portion of his time to the happiness of his daughter, but in the meantime builds a single-passenger spacecraft with life support for Rin to escape. He also successfully wipes any memory of him or Earth from her mind, instead programming these and a letter from him to come to her later in life in the hope that she would better understand the circumstance once she has matured. Just before the planet makes contact, he connects her to the simulation and launches the ship carrying her into space, where she has been for the past seven years.

Imagine being able to hear, feel and think – but not see or move. Around you, you can hear doctors and family members saying that you cannot understand or make decisions. This articles describes the difference between locked-in syndrome, where you appear vegetative but still have brain activity, and comas, where you would have no cognitive function nor motor responses as well as new technology used to identify those with locked-in syndrome and

communicate with them. While it may be difficult to judge the difference through the naked eye, those with locked-in syndrome actually have fluctuating stages of alertness throughout the day, so their brain is still active.

It provides kind of technology known as mindBeagle developed under the ComaWare project that is shaped into a soft cap and packed with EEG electrodes to measure brain activity. Once it figures out whether the patient as any cognitive function or not, doctors could communicate with people affect by the syndrome by asking yes/no questions. By playing high- and low-pitched tones, instructing the patient to count only the high tones and then measuring brain waves, doctors can learn whether their apparently comatose patient is in fact tuned into their environment.

Wearable EEG systems also promise to revolutionize epilepsy care. Around 65 million people worldwide live with epilepsy, which is usually diagnosed by a specialist reading an EEG scan which lasts around 20 minutes. However, experts believe this short assessment does not always collect enough information about the patient’s brain. If a longer EEG could be offered more frequently it could provide doctors with more information, making it easier to manage epilepsy with medication.

The solution: to develop a lightweight version of EEG “that’s small enough to be worn under a hat” so that patients can wear it for longer periods and allow doctors to collect the most pertinent data.

Prolonged social isolation can do severe, long-lasting damage to the brain. Robert King spent 29 years living alone in a six by nine-foot prison cell. He was part of the “Angola Three”—a trio of men kept in solitary confinement for decades and named for the Louisiana state penitentiary where they were held. King was released in 2001 after a judge overturned his 1973 conviction for killing a fellow inmate. Since his exoneration he has dedicated his life to raising awareness about the psychological harms of solitary confinement. His goal is to abolish solitary confinement.

There are an estimated 80,000 people, mostly men, in solitary confinement in U.S. prisons. They are confined to windowless cells roughly the size of a king bed for 23 hours a day, with virtually no human contact except for brief interactions with prison guards. According to scientists speaking at the conference session, this type of social isolation and sensory deprivation can have traumatic effects on the brain, many of which may be irreversible.

Most prisoners sentenced to solitary confinement remain there for one to three months, although nearly a quarter spend over a year there; the minimum amount of time is usually 15 days. Nevertheless, the UN bans solitary confinement for more than 15 days. It is associated with a 26% increased risk of premature death, largely stemming from an out of control stress response that results in higher cortisol levels, increased blood pressure and inflammation. Feeling socially isolated also increases the risk of suicide. For good or bad, the brain is shaped by its environment—and the social isolation and sensory deprivation King experienced likely changed his. Chronic stress damages the hippocampus, a brain area important for memory, spatial orientation and emotion regulation.

After learning about the mechanics of imagination in the human brain, take a stand in the debate over whether current generative AI models possess actual imagination and creativity. Would it be possible to train these models to become more imaginative over time? Be sure to consider concerns over “model collapse” and yet-to-be-achieved artificial general intelligence, then discuss with your team: what makes human imagination so difficult to replicate?

Is computational creativity possible? Some recent and remarkable milestones of generative AI foster this question:

-

An AI artwork, The Portrait of Edmond de Belamy, sold for $432,500, nearly 45 times its high estimate, by the auction house Christie’s in 2018. The artwork was created by a generative adversarial network that was fed a data set of 15,000 portraits covering six centuries.

-

Music producers such as Grammy-nominee Alex Da Kid, have collaborated with AI (in this case IBM’s Watson) to churn out hits and inform their creative process.

Humans are still at the helm and are still retaining authorship over their piece. However, AI image generators such as Dall-E can generate original outputs within seconds. It can now transpose written phrases into novel pictures or improvise in the style of any composer. Authorship in this case is perhaps more complex. Is it the algorithm? The thousands of artists whose work has been scraped to produce the image?

There are three types of creativity: combinational, exploratory, and transformational creativity.

-

Combinational – combining familiar ideas together

-

Exploratory – new ideas by exploring “structured conceptual spaces” and tweaking it

-

Transformational creativity – generate ideas beyond existing structures, creating something original

These different kinds of creativity are the heart of current debates around AI in terms of fair use and copyright – very much unchartered legal waters, so we will have to wait and see what the courts decide.

The key characteristic of AI’s creative processes is that the current computational creativity is systematic, not impulsive, as its human counterpart can often be. In fact, this is perhaps the most significant difference between artists and AI: while artists are self- and product-driven, AI is very much consumer-centric and market-driven – we only get the art we ask for, which is not perhaps, what we need.

Synthetic creativity on demand, as currently generated by AI, is certainly a boon to business and marketing. Recent examples include:

-

AI-enhanced advertising: Ogilvy Paris used Dall-E to create an AI version of Vermeer’s The Milkmaid for Nestle yoghurts.

-

AI-designed furniture: Kartell, Philippe Starck and Autodesk collaborated with AI to create the first chair designed using AI for sustainable manufacturing.

-

AI-augmented fashion styling: Stitch Fix utilised AI to capture personalised visualisations of clothing based on requested customer preferences such as colour, fabric and style.

As generative AI systems make significant inroads into creative industries such as art, writing, and music, there have been predictions of massive job loss confirmed by repeated waves of layoffs in 2023 and 2024 across the entertainment industry, many of which are explicitly linked to use of AI. Today, court cases and public discourse debate the legal and ethical practices of generative AI and training on copyrighted content without consent.

Generative AI models today use powerful machine learning algorithms to extract patterns from large volumes of popular content, to "learn" what is good art, what is good music, and what is compelling writing. If human tastes for art and creative content evolves over time, curated by stewards such as art critics and publishing editors, how do AI models do the same?

One answer might be that generative AI can also find new art styles or the next new genre of popular music, by scanning and filtering all possible genres of music and art. However, while developing and optimizing tools that explore and disrupt style mimicry, we find that the number of distinctive styles in art and music are nearly infinite. How will generative AI find the next version of hip-pop, a musical genre that has transformed the music industry and influenced genres as disparate as country music? How would future AI models find ways to identify and transform that human condition into music, so that it can connect with other humans sharing similar emotions and experiences?

Part of this is because appreciation of music and other artistic mediums is subjective, and fundamentally based on human tastes. For an AI model to understand and predict how humans do or do not appreciate a specific style, it would have to first understand human emotions. Taking this perspective, it is not hard to understand why current research predicts that AI models trained on their own input will eventually collapse. If each generation of a generative AI model is trying to approximate and mimic the complex human appreciation of an art form, then its output will be a facsimile with some amount of error.

A recent study warns that AI models, particularly large language models (LLMs) like OpenAI's ChatGPT, may face a significant issue known as "model collapse" due to their increasing reliance on AI-generated content for training. As these models exhaust available human-generated data or encounter restrictions, they may begin training on their own outputs, leading to degraded performance and nonsensical results. Model collapse occurs in two stages: first, in the early stage, models trained on outputs from other models start to oversample well-understood aspects while neglecting less understood ones. In the late stage, errors from earlier models propagate through successive models, resulting in misinterpretations and increasing errors.

The study identifies three main types of errors that can occur: architecture errors, which arise from structural issues in the model that hinder its ability to capture data complexities; learning process errors, which stem from biases in training methods that lead to systematic mistakes; and statistical errors, which occur when there is insufficient data representation, causing incomplete predictions. The implications of relying on AI-generated content could slow down performance improvements and

disproportionately affect underrepresented data, raising concerns about the fairness and inclusivity of AI models. Researchers emphasize the need for careful data management to maintain model integrity and avoid bias.

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) refers to a theoretical AI system that can perform cognitive tasks at a level comparable to humans. While recent advancements in AI, particularly in generative tools like ChatGPT, are impressive, they primarily function as prediction machines trained on extensive datasets without the nuanced reasoning and emotional understanding characteristic of humans. Experts believe that achieving AGI is still decades or even centuries away, with some predicting it may not be possible this century.

To realize AGI, AI systems must master several key capabilities, including visual and audio perception, fine motor skills, natural language processing, problem-solving, and social and emotional engagement. These abilities would enable AGI to interact with humans meaningfully and understand complex concepts. Future access to AGI may evolve from traditional interfaces to more immersive technologies, such as augmented reality or brain implants, facilitating deeper human-machine interaction.

Several factors could accelerate the development of AGI. Innovations in algorithms, particularly those focusing on embodied cognition, are essential for enabling AI to learn from its environment like humans. Computing advancements, especially in quantum computing, will also be crucial for handling the complex processing required for AGI. Additionally, a surge in connected devices and new data sources will enhance training capabilities, allowing AI systems to adapt more effectively.

Although AGI is still a distant goal, executives should prepare for rapid AI advancements by staying informed about developments and investing in AI technologies. Emphasizing human-centered approaches will ensure that employees are equipped to work alongside AI, while addressing ethical and security implications is vital for responsible implementation. By taking these proactive steps, organizations can better position themselves for the future of AI and its potential impact on their operations.